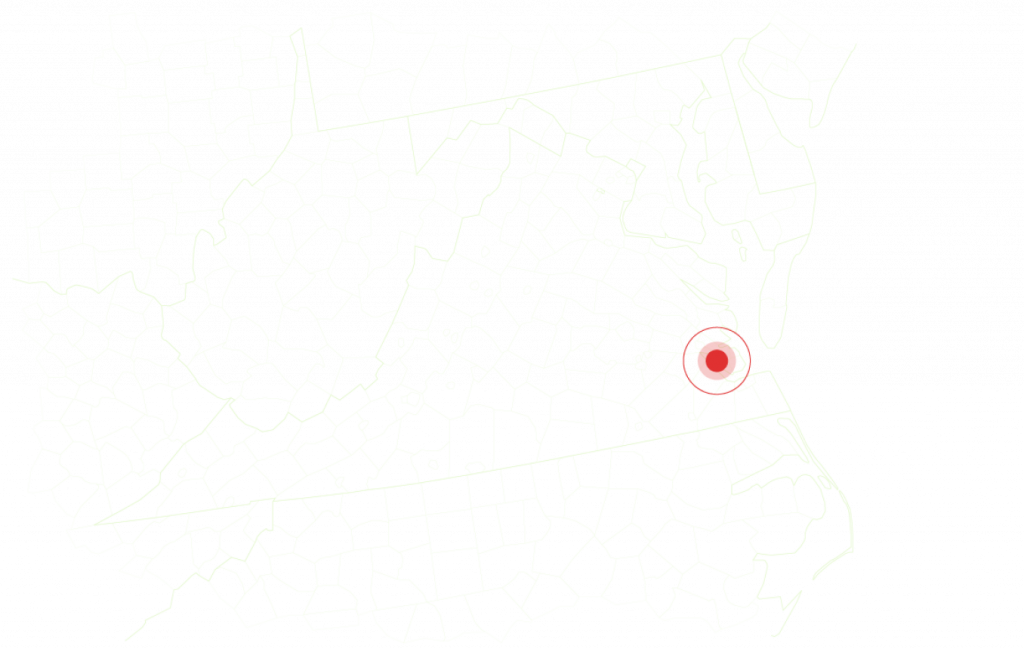

Dispossession of Land

from Indigenous Peoples:

1607 – Present Day

When settlers arrived in what is now Virginia in 1607 and established Jamestown as the first permanent English settlement in the Americas, the land they occupied was part of the Paspahegh tribe.

The Paspahegh were among the 15,000 people and 30 tribes comprising the Powhatan Confederacy, which included the entirety of the Virginia Tidewater region and much of the Eastern Shore.

While the leader of this vast region, Chief Wahunsunacawh (known to the English as Chief Powhatan), and John Smith, a leader of the Virginia colony, were both interested in establishing a trading relationship, conflict arose early; not only were the settlers seeking to expand their territory, but Smith also failed to keep his promise to move the colony to Capahosick.

Tensions and bloodshed increased over the following years, and in 1610, Chief Wahunsunacawh expressed to Smith that “many informe me your comming is not for trade, but to invade my people and possesse my Country.”[#01]

His words would prove to be prescient. By May of 1611, the Paspahegh tribe, one of the first to engage with English settlers, was no more. [#02] Over the next three centuries, Native Americans were subject to colonial and then federal policies of displacement, genocide, and cultural assimilation.

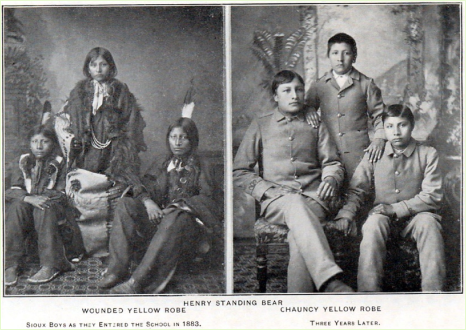

Top: Three young Lakota Indian boys pictured (left) wearing their tribal clothing upon their arrival at Carlisle Indian School, and (right) a short time later wearing their school military-style uniforms, ca. 1900.

Bottom: Tom Torlino-Navajo, pictured as he entered Carlisle Indian School in 1882 (left), and a short time later wearing his school uniform (right).

In 1860, the Bureau of Indian affairs began the practice of removing American Indian children from their families to attend schools designed to assimilate them into mainstream society. Parents weren’t legally allowed to refuse their children’s placement in off-reservation schools until 1978. [#03]

The Dawes Act of 1877 coerced Native people into Western models of property ownership instead of collective tribal ownership. This included forcing them to sell their tribal land to acquire cash and to adopt Western farming techniques.

American Indians are the largest private landholders in the US, yet they have the highest poverty rate of any racial group. This is due in part to federal policy putting the wealth of Native people (including the land, natural resources, and income generated from such resources) under the control of the federal government, depriving tribes of untold amounts of revenue. [#04]

Early rendering of the wall for which Wall Street was named.

The “wall” after which Wall Street was named was built by enslaved people.

It kept members of the Lenape tribe from reclaiming their land.

Indian homelands

(1776 to present)

Indian Reservations

Wall Street Established

as an Official Trading

Post of Enslaved Peoples:

1711

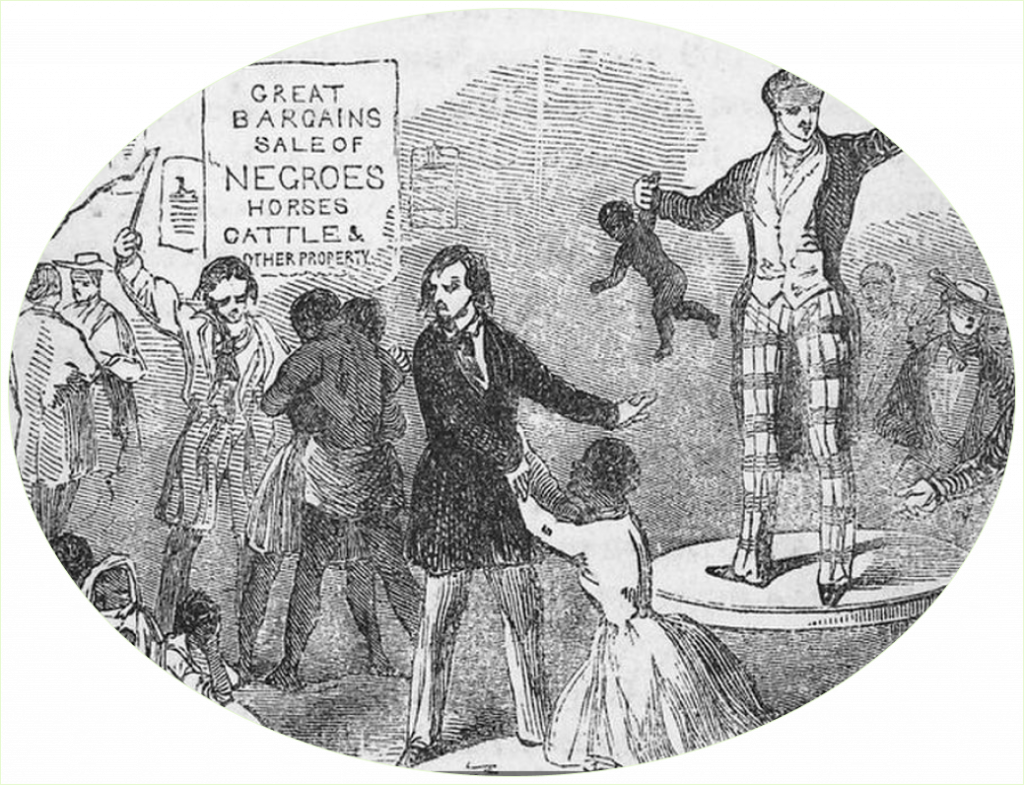

Illustration of enslaved people being sold at auction.

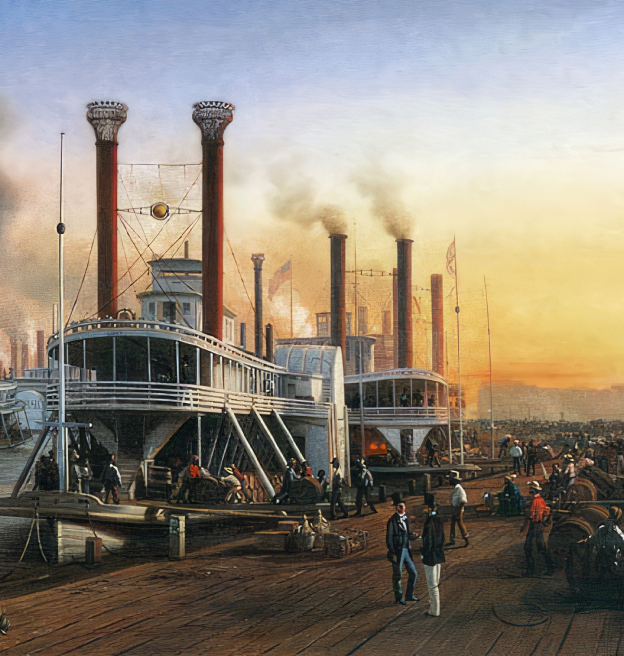

Less than 60 years after enslaved Africans built the wall for which Wall Street would be named, New York would erect a market at the corner of Wall and Water Streets, designating it as the city’s official slave trading post. [#05]

Later, big banks began a practice of selling “securitized slave bonds” to investors. These bonds generated revenue for Wall Street investors as enslavers made repayments of mortgages on enslaved people.

The bonds were “securitized” to pool debt from many borrowers so that the debt could be sold off in uniform chunks, reducing the risks inherent in lending to one person at a time, and in trading in human life and human productivity.

Lithograph of Canal Bank, which, with Citizens Bank, accepted approximately 13,000 enslaved people as collateral and “repossessed” roughly 1,250 enslaved human beings.

Citizens’ Bank and Canal Bank of Louisiana collectively accepted approximately 13,000 enslaved people as collateral and directly owned more than 1,200 human beings. Both are predecessor companies of what is now J.P. Morgan Chase.[#06] Wachovia Bank (owned by Wells Fargo)[#07] and Bank of America [#08] have also acknowledged profiting from ties to slavery.

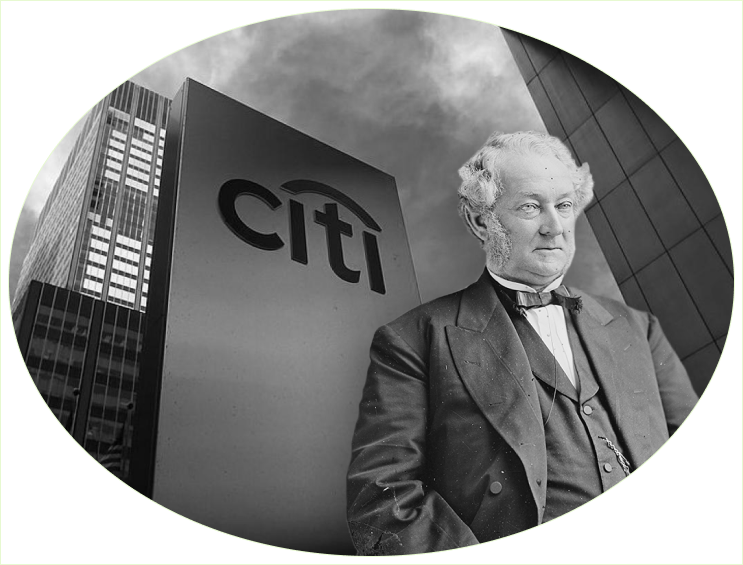

Moses Taylor, president of National City Bank of New York–now Citibank–and participant in the illegal slave trade.

At the time of his death, the estate of Moses Taylor, who served as the president of City Bank (now Citibank) for 18 years, was valued at roughly $70 million (or around $1.9 billion in today’s dollars). [#09] He remains one of the richest Americans of all time, thanks in large part to his illegal financing of the slave trade.

The New York Stock Exchange emerged from the Buttonwood Agreement. The agreement, signed by 24 wealthy white traders to regulate their exchanges, covered transactions related to the slave trade, from insurance and shipping to cotton.

The selling of human beings was by no means the only way the city benefited from the cotton trade, however. Ultimately, 40 cents from every cotton-generated dollar went to New York City to pay for the financing, transportation, and insurance of enslaved people and the cotton and other products they produced. These revenues were essential in making New York the financial and commercial center it is today. [#10]

Nearly 10 million homeowners lost their homes to foreclosure sales in the U.S. between 2006 and 2014.

The bundling of a good (in this case, human lives) into a financial product for large banks like Baring Brothers & Co. (later bought by ING) to sell was remarkably similar to the securitized bonds, backed by mortgages on US homes, that led to the economic collapse of 2008.

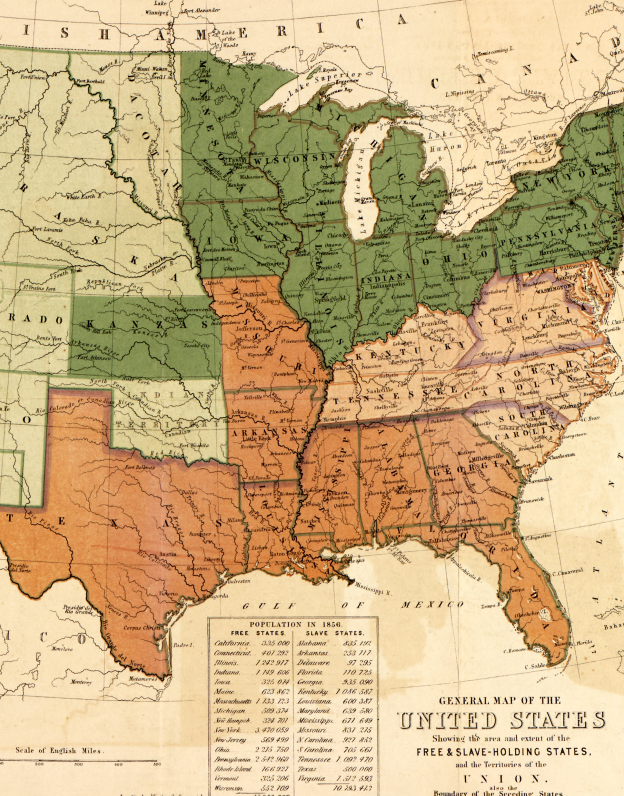

Invention of the Cotton

Gin Accelerates the

Expansion of Slavery:

1794

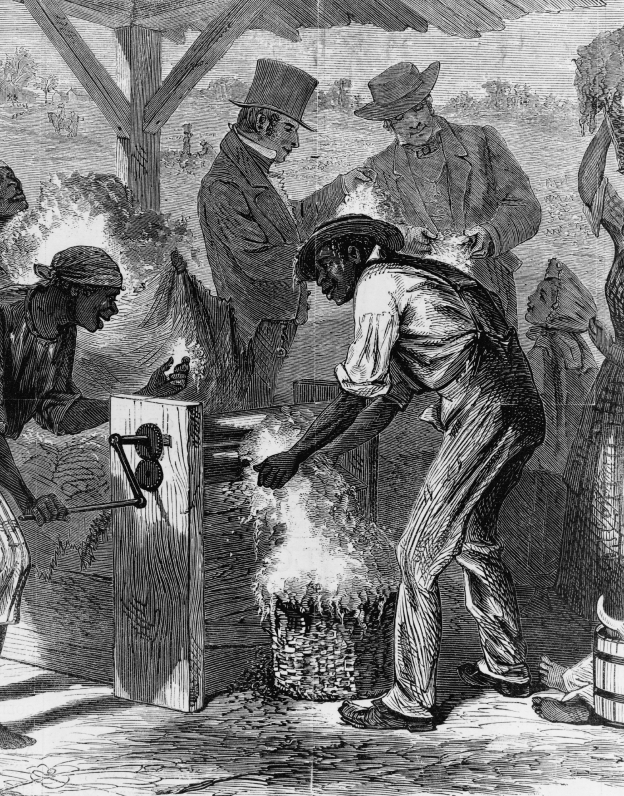

Illustration of enslaved people gathering cotton on a southern plantation.

Before the patenting of the cotton gin in 1794, it was impossible for enslaved workers to clean as much cotton as they could grow, with the average person able to remove seeds from only around one pound of cotton a day.

A hand-cranked gin, in contrast, could clean 50 pounds in the same amount of time. [#11] Recognizing the potential for exponentially increasing profits, enslavers aggressively acquired more land and more enslaved labor, helping drive the number of slave states from six in 1790 to 15 in 1860.

At that point, roughly one in three southerners was enslaved. Their unpaid labor produced three-quarters of the world’s cotton supply, which was primarily shipped to England and New England to be made into cloth. [#12]

With enslaved people consigned to increasingly larger plantations, enslavers sought to further increase productivity through torturing workers to meet ever-higher quotas. Enslavers’ sense of an endless supply of land and labor reduced competition, which made them willing to document and share the most effective torture methods with each other. [#13]

These strategies were so effective that “within 10 years after the cotton gin was put into use, the value of the total United States crop leaped from $150,000 to more than $8 million.” [#14]

As the nation headed into the Civil War, “cotton that was grown and picked by enslaved workers was the nation’s most valuable export.” [#15] The enslaved workers themselves made up 48% of the South’s total wealth in 1860. [#16] Given their ownership of other humans and their lifetime of labor, it is perhaps unsurprising that there were more millionaires per capita in the Mississippi Valley than anywhere else in the country by the war’s start. [#17]

Choctaw Nation Forced

to Abandon Ancestral

Lands for “Indian

Territory”: 1831

In 1831, the Choctaws became the first nation to be forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in what is now Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

Choctaw

This expulsion followed the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, which “required the government to negotiate removal treaties fairly, voluntarily, and peacefully” [#18] with tribes willing to exchange their tribal land east of the Mississippi River for land in the “Indian Territory” of present-day Oklahoma.

Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States, signed the Indian Removal Act into law on May 28, 1830.

The legal constraint of peaceful, non-coercive negotiations did nothing to stop the sitting president, Andrew Jackson, from using threats and military might to take tribal land by force. In short order, the Choctaw would be followed by the Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations on the long walk that one Choctaw leader described to an Alabama newspaper as a “trail of tears and death.”

The millions of acres that these tribes had cultivated and lived on for generations were then sold at deeply discounted rates ($38 per acre in today’s dollars) to white settlers. [#19]

22,000 of the roughly 60,000 Native Americans—or as many as 1 in 3—who were made to walk hundreds of miles to unfamiliar land, died along the journey. [#20]

A former Confederate soldier who participated in the removal is said to have commented, “I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.” [#21]

Lehman Brothers’

Cotton Exchange: 1858

Lehman Brothers, a former Fortune 500 global financial services firm, was founded in 1850 in Montgomery, AL by Henry, Emanuel, and Mayer Lehman.

By offering mortgages on enslaved people, banks enabled enslavers to expand their workforce even when they had limited cash.

The business evolved into a cotton brokerage firm and opened an office in New York in 1858, later helping establish the Cotton Exchange.

When Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, it held over $600 billion in assets.

The banking industry reaped massive profits from Southern plantations that had amassed wealth through the labor of enslaved Black people—and from other methods of exploitation after slavery was outlawed.

Lehman Brothers used this capital to diversify and expand over time. In partnership with Goldman and Sachs’ Henry Goldman, the company underwrote and funded, among other things, several department stores, including Woolworth’s, Sears, and Macy’s. [#22] Lehman Brothers later was at the center of the 2007 mortgage and 2008 banking and financial crises. When the business filed for bankruptcy in 2008, it marked one of the largest bankruptcies in history.

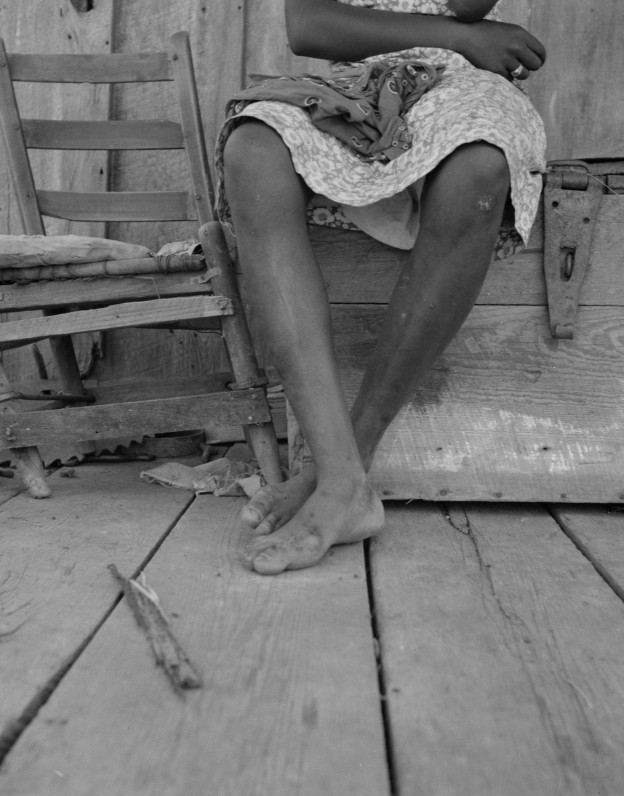

Sharecropping and Debt

Peonage: 1870s-1940s

In the fall of 1865, President Andrew Johnson overturned General William Sherman’s Special Field Order Number 15, which promised to newly freed enslaved people that “each family shall have a plot of not more than 40 acres of tillable land.” As a consequence of Johnson’s revocation, land seized by the Union army was returned to its former Confederate owners, forcing many Black families to become sharecroppers.

The plantation elite recaptured some of what they lost with the end of slavery by forcing many Black farmers into sharecropping, a form of “debt peonage, under the sway of cotton kings who were at once their landlords, their employers, and merchants.” [#23]

“Tools and living necessities were lent to sharecroppers for a price paid out of whatever profit was made from the crop. When farmers were deemed to be in debt—and they often were—the negative balance was then carried over to the next season.

Anyone who protested this arrangement did so at the risk of grave injury or death. Refusing to work meant arrest under vagrancy laws and forced labor under the state’s penal system.” [#23] Poor white people also had few options.

The front page of The Chicago Defender, October 11, 1919, documenting the killings of Black families in Elaine, Arkansas. This excerpt was found in the scrapbook of Arkansas Governer Charles Brough.

By 1880, one-third of white farmers were sharecroppers or tenants, as were 75% of Black people. [#24]

When white landowners massacred hundreds of Black sharecroppers in Elaine, Arkansas in September 1919, it was because some of them were attempting to organize to demand fairer profit sharing and an accounting of the supposed debts that were assigned to them.

Prison Labor:

1870s - Present Day

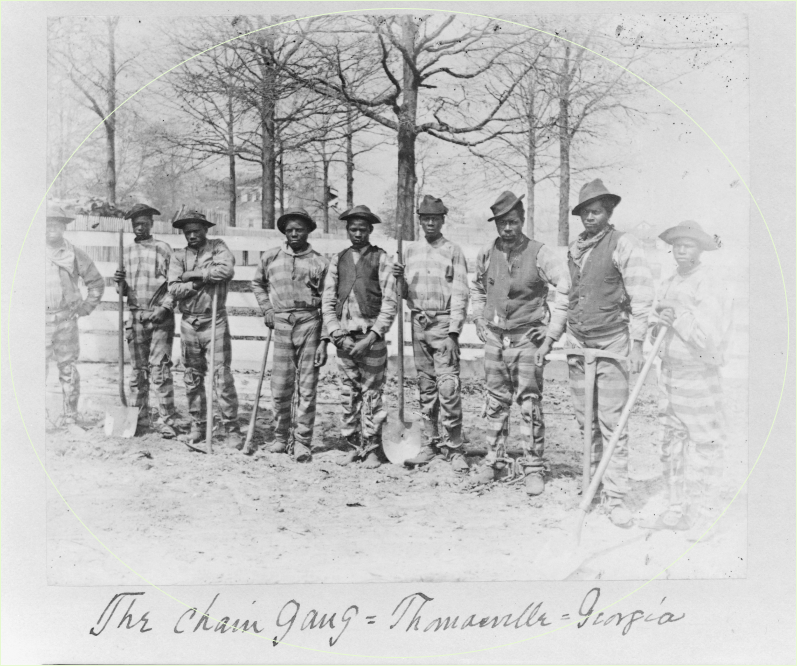

A chain gang in Thomasville, Georgia.

From the late 1870s through the mid-twentieth century, thousands of African-American men were arrested and forced to work off outrageous fines by serving as unpaid labor in subhuman conditions, where they were often subject to torture. [#26]

States made a profit leasing convicts to private businesses and provincial farmers. Inconsequential actions were often a pretense for arrest, with unemployment being made illegal in Virginia as part of Black Codes. (Black Codes were established to maintain and reinforce racial hierarchy.) Even being found on someone else’s land could result in a larceny charge. [#27]

If the accused could not pay the steep fine, they were imprisoned. Changing employers without permission, false pretense, and “selling cotton after sunset” were all arrestable offenses in rural Alabama by 1890. [#28]

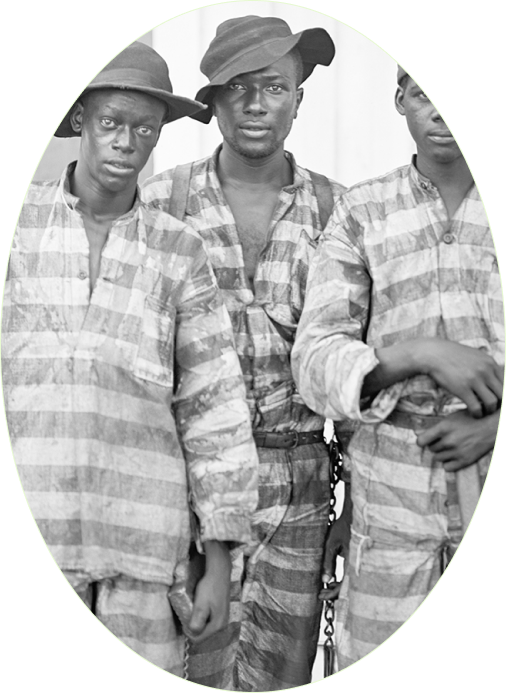

A southern chain gang, circa 1903.

A growing number of prisons are run by private companies, and their investors have included private equity firms and the big banks. Inmates at private prisons often work for little to nothing, while investors turn a profit. This system creates a perverse incentive to increase detention. [#30]

Railroads and Chinese

Laborers: 1880s-1890s

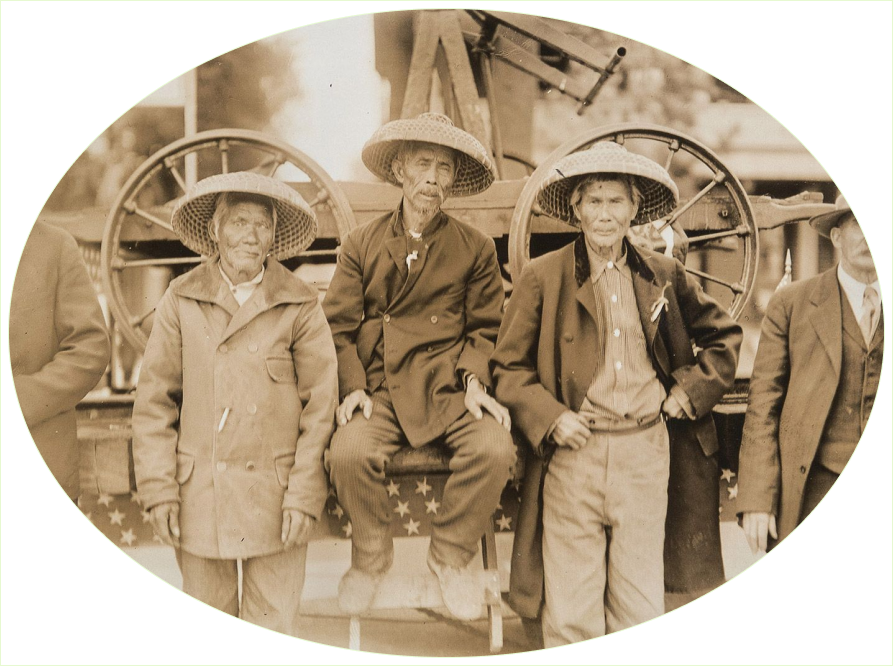

Chinese transcontinental railroad workers in 1869.

Wanting to profit off of the West coast economic boom, railroad companies like the Central Pacific Railroad started to hire laborers. They couldn’t keep workers for very long, however, due to low wages and horrendous working conditions.

After a wage dispute was launched by Irish workers, the company started targeting Chinese migrants. The Central Pacific Railroad recruited more than 12,000 Chinese laborers, paying them less (at $27-30 per month) than the $35 plus free room and board they paid to Irish workers. [#32]

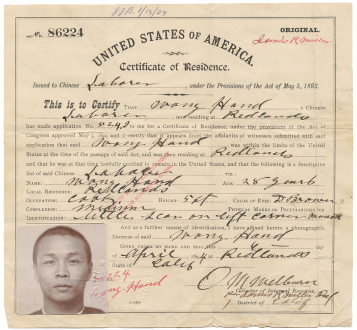

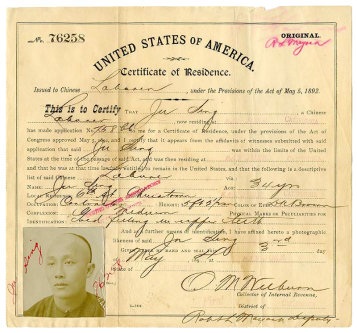

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in response to racist claims that Chinese immigrants were responsible for declining wages, even though they represented only .002% of the population.

After the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese immigrants were required to prove their legal presence in the U.S. by having government-issued identification cards on their persons at all times or risk facing deportation or being sentenced to hard labor.

The law banned the immigration of Chinese workers and made them ineligible for naturalization. It was the first major attempt to restrict the flow of workers coming to the U.S. Chinese immigrants and their American-born offspring were not allowed to become U.S. citizens until 1943. [#33]

Railroad companies were major players in the growth of Wall Street. They were among the first U.S. companies to issue stocks and bonds after profiting from government subsidies and land grants to expand across Native land.

Congress establishes the Internal Revenue Service (IRS): 1913

IRS Headquarters, Washington, DC

In 1913, Congress passed the 16th Amendment, creating what is today known as the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

Before then, taxes looked very different than they do today.

Between the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the start of the Civil War in 1861, there was no national income tax. Revenue came mainly from excise taxes (like on tobacco) and tariffs (like those on enslaved people “imported” into the country).

Excise taxes, like those on tobacco and alcohol, made up a large portion of government revenue

On the state level, nothing contributed more to government revenues than slave taxes, especially in the South.

Percentage of state tax revenues from slavery

Percentage of state tax revenues from slavery

During that time, slave taxes brought in so much revenue that small farmers paid almost no direct taxes at all. It was a progressive tax system but it was also a tax system based on the exploitation of stolen labor on stolen land.

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, the US government needed to raise more revenue. So, the Revenue Act of 1861 was passed, creating the nation’s first income tax. Incomes over $800 (~$28,700 today) were taxed at 3%.

In the modern era, taxes changed significantly.

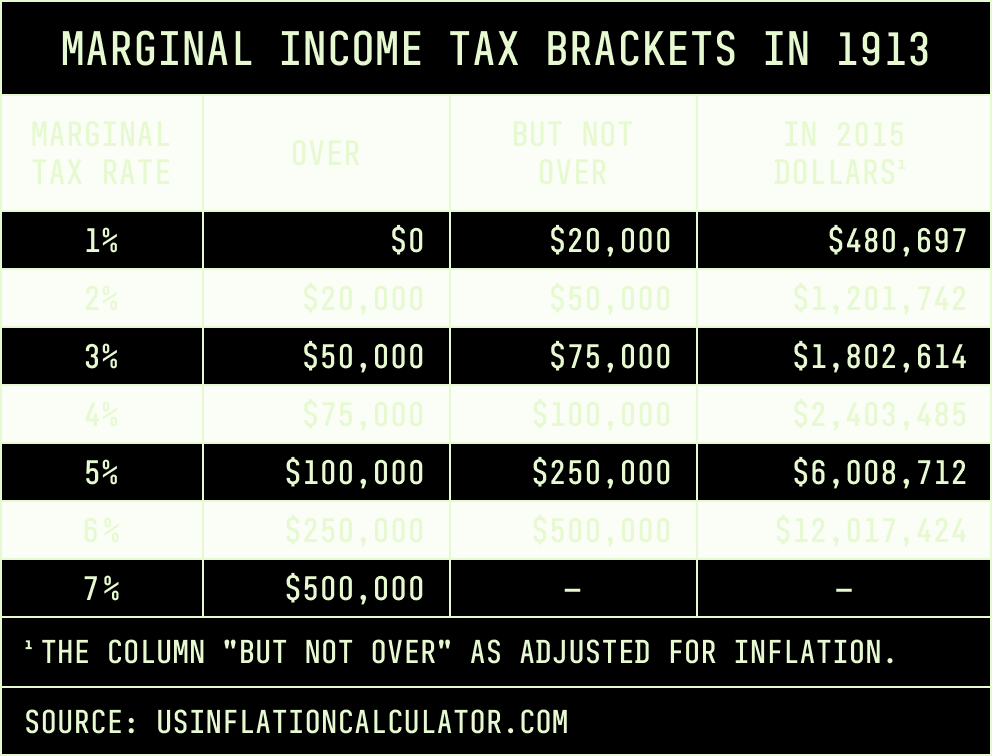

The tax structure created in 1913 was initially a progressive one and mostly taxed the wealthy. Less than 1% of the population paid taxes in 1913. The highest marginal tax rate at the time was a mere 7%. The marginal tax rate only applies to the top portion of someone’s income, so even people with the very highest incomes didn’t pay 7% on all of their earnings.

Marginal Income Tax Brackets in 1913.

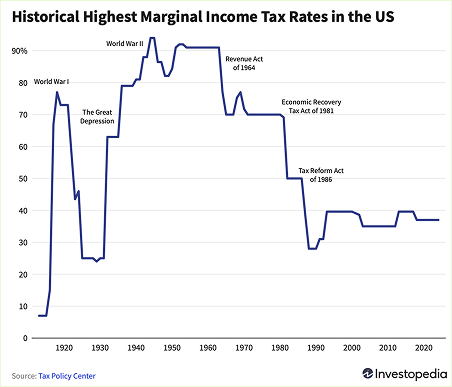

By 1918, the marginal tax rate was 77%. During the final years of the next World War, 1944 and 1945, the top marginal tax rate was 94%.

That didn’t last long.

Highest Marginal Income Tax Rate in the U.S. over the past 100 years

The taxes paid by the wealthy have plummeted over time.

Taxes continue to plummet for the wealthy, while those with greater need see no relief

Lowering the tax responsibility for those with the most expendable income has consequences for everyone.

When taxes decrease, so do revenues, leaving less money to fund essential services.

Unlike the federal government, states are required to have balanced budgets. This means states often cut funds for cities and counties or raise revenue by adopting regressive taxes like fines and fees. People who are Black, Indigenous, and of color are the most disadvantaged by those decisions.

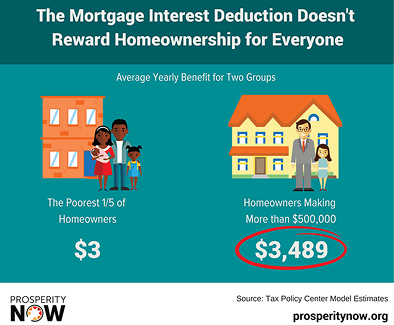

Another inequity in the federal tax structure is the mortgage interest deduction. White households receive over 75% of that tax benefit.

Inequity is built into the tax structure

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was the most significant tax legislation passed in the last 30 years. While it increased the child tax credit, the overwhelming majority of the law benefited the wealthy. It cut the corporate tax rate from 35 to 21%,

increased the estate tax exemption, making it easier for the wealthy to pass on more money to their descendants untaxed,

and cut the top marginal tax rate from 39.6 to 37%.

The TCJA didn’t lead to more jobs, fairer taxes, or bigger paychecks

Overall, billionaires saw their wealth grow, while working people gained almost nothing from the bill.

Elon Musk, estimated net worth of $356.7B, bought Twitter for $44B.

Jeff Bezos, estimated net worth $221B, bought a $500M super yacht

In 2025, Congress passed sweeping legislation that made these tax cuts permanent and slashed public budgets to pay for them.

There are ways to right-size our tax system, though:

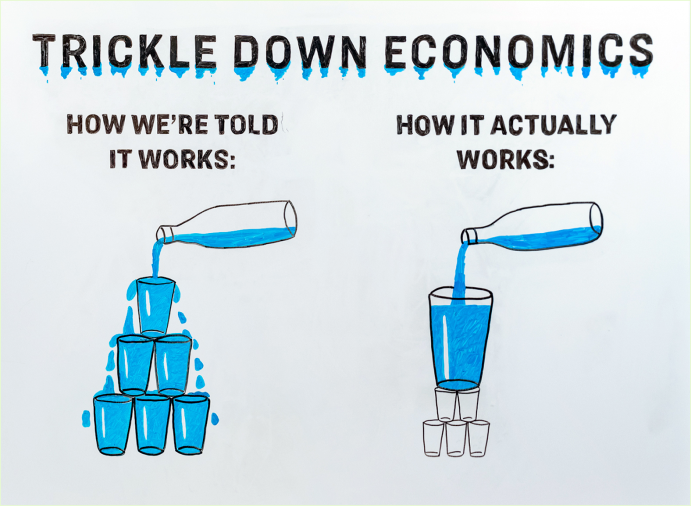

Trickle down economics does not work

- Push to reverse tax cuts for the rich.

- Stop rewarding wealth over work.

- Reform policies so that the wealthy and corporations pay their fair share.

- Get rid of regressive taxes which put an outsized burden on the poor and middle class.

To get involved with our fight for an economically and racially just financial system,

please fill out this form.Sign up for our newsletter:

Americans for Financial ReformTulsa Black Wall Street Massacre: 1921

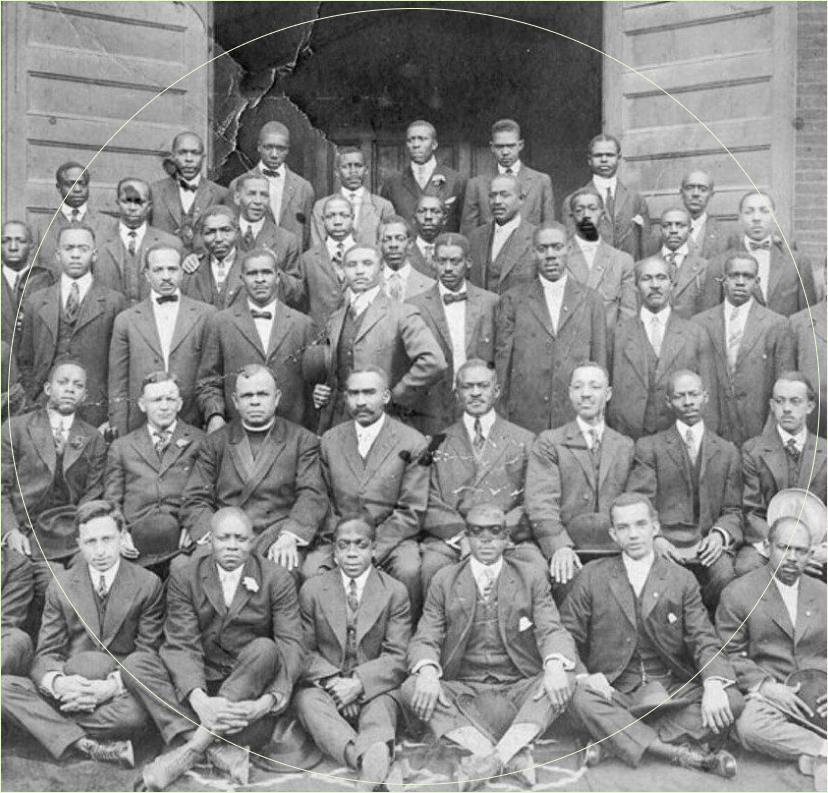

Black business leaders of the Greenwood community of Tulsa (pictured.) The 600+ businesses of Black Wall Street included 30 grocery stores, 21 churches, 21 restaurants, two movie theaters, schools, libraries, law offices, a hospital, a bank, a post office, and a bus system. Community members also owned six private airplanes. [#34]

In the 1920s, Tulsa, Oklahoma was 12 percent Black. Most of the Black population lived in Greenwood, which was often called the “Negro Wall Street of America” because of the prominent citizens (including at least three millionaires) who accumulated wealth through the oil boom.

Unwelcome downtown, except when working, Black residents of Greenwood had established their own newspapers, theaters, cafes, stores, and professional offices.

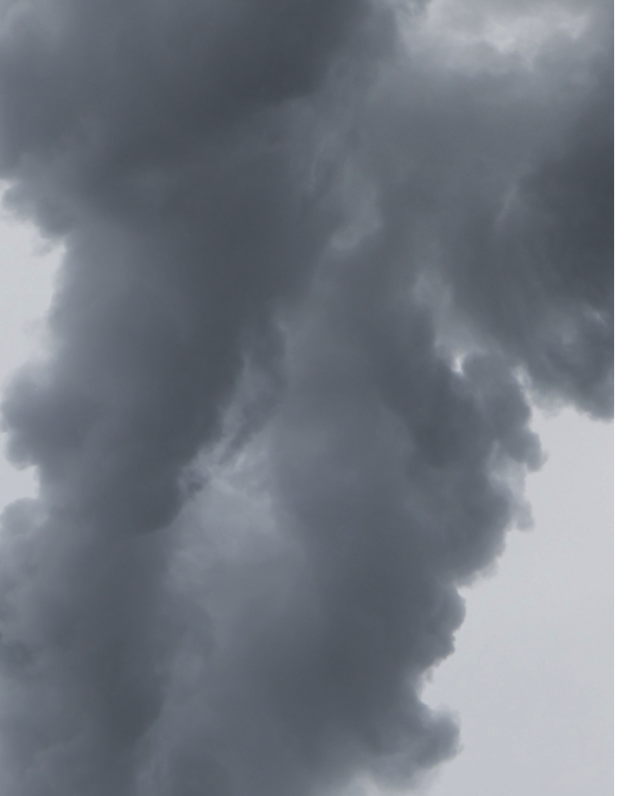

Smoke billowing over Tulsa during the massacre, 1921

In the early morning hours of June 1, 1921, Black Tulsa was looted and burned by white rioters.

Governor James Robertson declared martial law and called in the Oklahoma National Guard. Guardsmen assisted firemen in putting out fires, took imprisoned Black residents out of the hands of vigilantes, and imprisoned all Black Tulsans not already interned.

Over 6,000 people were held at the Convention Hall and the Fairgrounds, some for as long as eight days. [#35]

White rioters destroyed an estimated $200 million in Black property in today’s dollars.

Stock Market Crashes, Ushering in the Great Depression: 1929

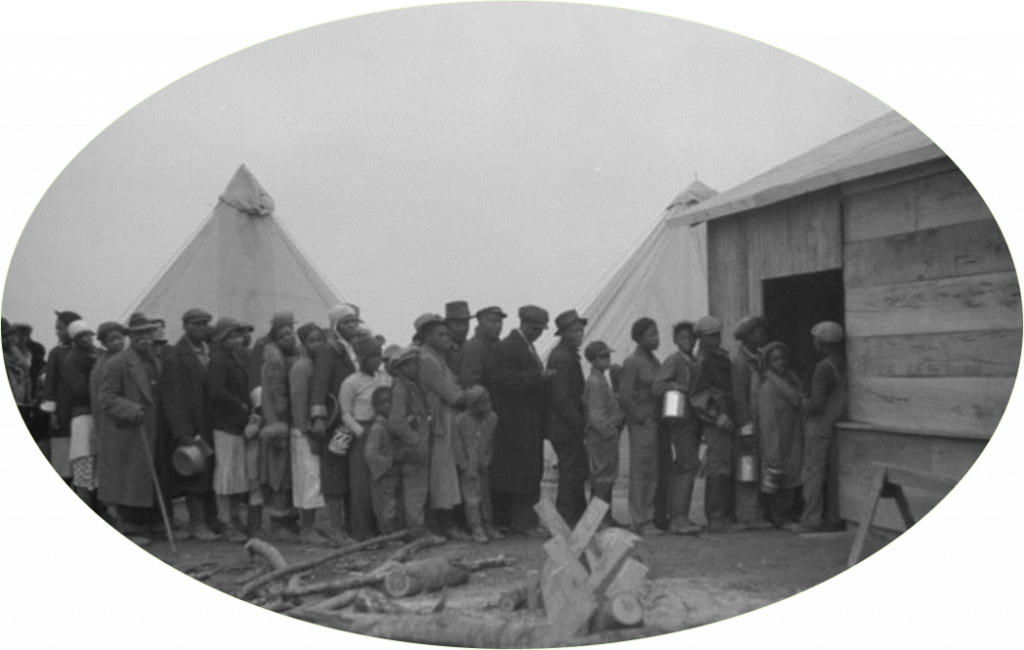

Flood refugees in line for food, at the time of the Louisville flood in 1937.

The Great Depression devastated the United States, leaving no population untouched. No group, however, was as negatively impacted by this economic catastrophe as African Americans were.

In some Northern cities, white people called for Black workers to be fired from any job as long as there were white people out of work. Racial violence increased, especially in the South, where there was a significant rise in lynchings. [#36]

Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act into law on August 14th, 1935.

Much heralded measures to address the economic hardships experienced during the Great Depression, notably the New Deal, would exclude Black people either overtly or in practice.

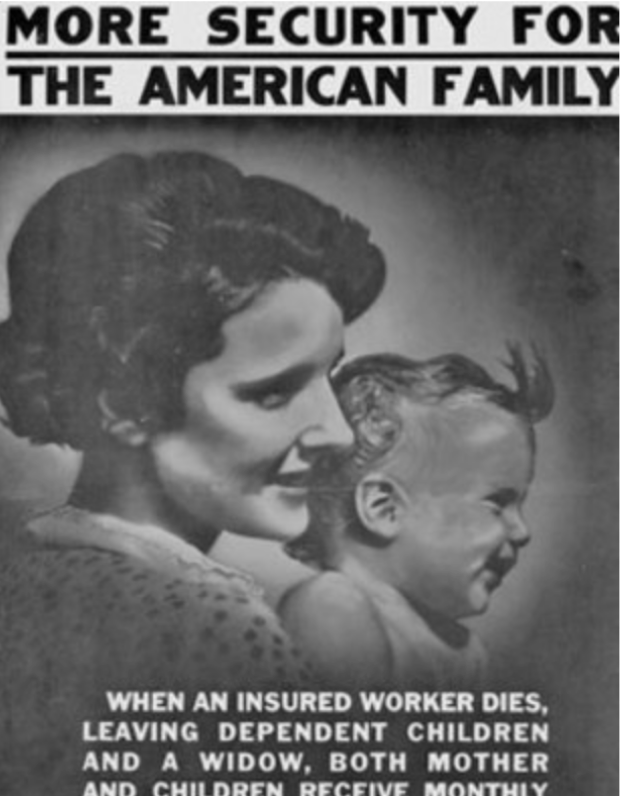

Social Security, for example, didn’t apply to agricultural and domestic workers—positions likely to be held by Black people. Consequently, while 27% of white people were ineligible for Social Security in 1935, 65% of Black people were excluded, as were 70-80% of Black people in the South. [#37]

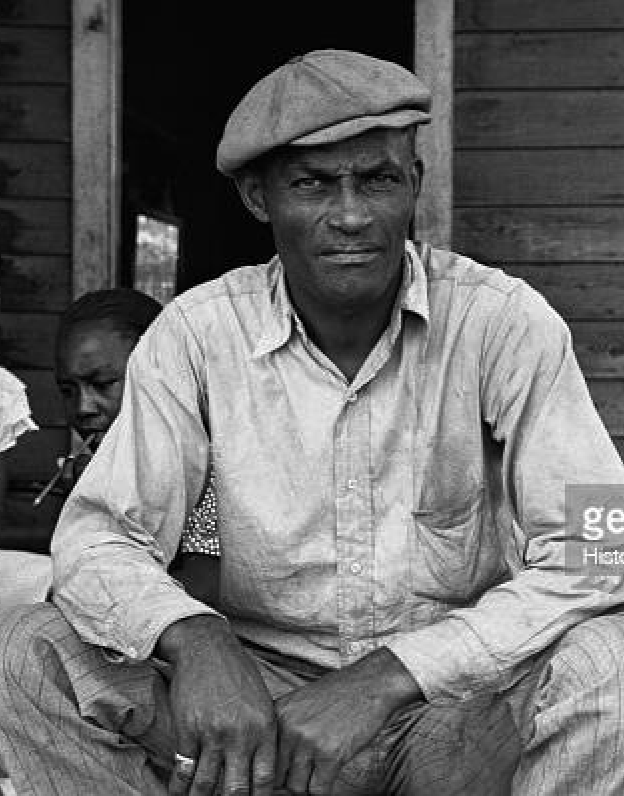

Black women complete a training program to work as maids and household servants. New Orleans, 1939.

This was especially harmful to Black women, who, “compared with other women the United States, have always had the highest levels of labor market participation regardless of age, marital status, or presence of children at home…. Black women have been the most likely of all women to be employed in the low-wage women’s jobs that involve cooking, cleaning, and caregiving.” [#38]

LA Police "Repatriate" Mexican Americans and Immigrants at La Placita Park: 1931

A Los Angeles newspaper published a front-page story about La Placita the day after the raid.

On a Sunday afternoon in February 1931, two police officers blocked each of the two entrances to Los Angeles’s La Placita Park and “rounded up all the people with brown skin,” [#39] demanding proof of citizenship or legal residency.

Mexican and Mexican-American families wait to board Mexico-bound trains in Los Angeles on March 8, 1932.

Those who couldn’t immediately prove their right to be in the country were detained, with some being made to board one of the flatbed trucks lining the park’s perimeter. The trucks were taken to the local train station where, regardless of documentation status, Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans were forced to board chartered trains that would deposit them deep into Mexico. [#40]

Many U.S. citizens who had never lived in Mexico were unable to return home for years.

Relatives and friends wave goodbye to a train carrying 1,500 people being expelled from Los Angeles back to Mexico in 1931.

This was one of the most visible of the “repatriation raids” that took place throughout the 1930s. As the Great Depression wreaked havoc on the job market, people of Mexican descent were scapegoated both for taking jobs some claimed would otherwise be going to white Americans and for overwhelming government relief programs.

In reality, less than 10% of recipients of government aid were Mexican immigrants or Mexican Americans, and studies decades later would suggest that these repatriation drives actually harmed the economy because they reduced the demand for other jobs.

Official Presidential portrait of Herbert Hoover, the 31st President of the United States.

While these raids were not explicitly part of federal policy, the Herbert Hoover administration reimbursed municipalities for the cost of chartering trains and buses, and its campaign of “American jobs for real Americans” indicates more than tacit support.

Hoover also convinced a number of large companies, including the Ford Motor Company, U.S. Steel, and Southern Pacific Railroad, to lay off employees of Mexican descent.

Conservative estimates state that between one million and 1.8 million people were deported, as many as 60% of whom were U.S. citizens. [#41]

The Home Owners Loan Corporation Develops Redlining: 1933

The federally-sponsored Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created in 1933 with the primary function of refinancing mortgages that were going into foreclosure. At the time, mortgage foreclosures were occurring at a rate of almost 50%.

The HOLC refinanced approximately one million homes, representing close to 20% of US mortgages between 1933 and 1936. [#42]

By 1962, that amount had increased to $120 billion. Less than 2% of HOLC’s loans went to nonwhite homeowners. [#43]

This is because the HOLC assigned color- and grade-coded designations to neighborhoods to indicate whether they were worthy of mortgages. Neighborhoods designated as “A” or “green” were considered the best places to provide loans, and those designated as “D” or “red” were considered “hazardous” places to provide loans. [#44]

The Seattle chapter of the Congress for Racial Equality organized protests at the offices of Picture Floor Plans because of the business’s discrimination against people of color.

Communities of color were uniformly “redlined.” Even “a single Black household in a middle-class area could make the whole neighborhood ‘risky’ for mortgage loans in the eyes of the federal government.” [#45]

The HOLC codified patterns of racial segregation and disparities in access to credit. [#46] While the practice would become illegal in 1968, unspoken practices, poor enforcement, and, more recently, the advent of discriminatory computer algorithms have stepped in to accomplish a similar purpose. [#47]

Report on “Pinklining” Reveals How Wall Street Targets Women for Toxic Loans: 2016

Even though women make higher student loan payments than men, it takes them an average of two years longer to pay off those debts. [#48]

Wall Street has long taken advantage of women, especially women of color, historically having lower incomes and less wealth.

The financial industry has targeted women—who have disproportionate responsibility for caregiving, disproportionate harm from cuts to public services, and an increasing need to borrow for basic needs like healthcare—to sell them predatory lending products in a practice called “pinklining.”

In the lead-up to the 2008 financial crisis, Black women were 256% more likely than white men to receive subprime loans.

Single women have greater amounts of debt than men in every category—education debt, vehicle debt, mortgage debt, and credit card debt. And they are often targeted for toxic loans with higher interest rates or hidden fees, be they subprime home mortgages, payday lending with 400+% average interest rates, or student loans.

When they retire, the wealth gap becomes painfully clear: fewer women participate in the stock market than men and fall behind in 401k contributions. The systemic gaps in resources, opportunities, and wages have generated an extraordinary transfer of wealth from women to the financial sector. [#49]

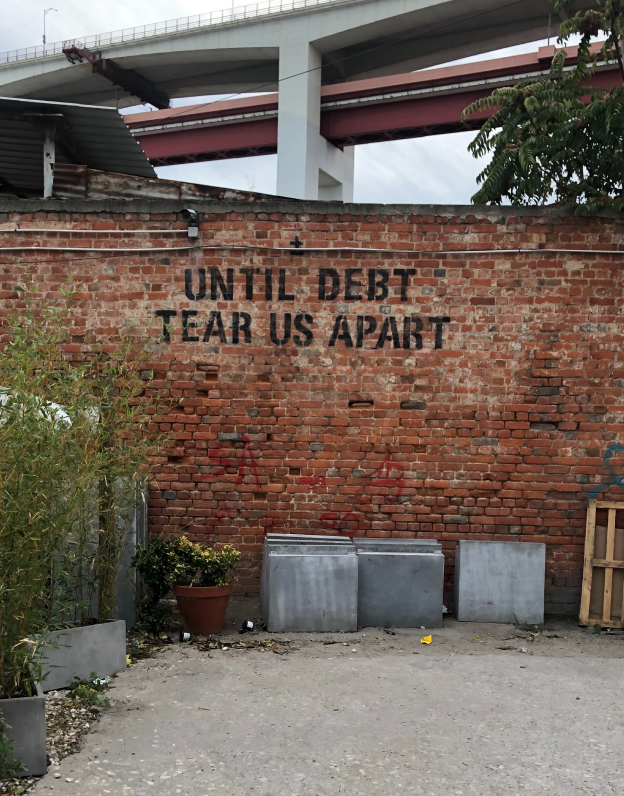

Explosion Highlights Risks of Wall Street Chemical Plant Ownership: 2019

Image of the November 27, 2019 explosion and fire at the TPC Group chemical plant in Port Neches, Texas.

The day before Thanksgiving 2019, a chemical plant operated by the TPC Group and owned by the private equity firm SK Capital exploded in Port Neches, Texas.

The explosion spewed contaminants that forced over 50,000 people to evacuate, leaving the community with the lingering aftereffects of an industrial disaster.

The chemical plants SK Capital owns in Texas have a long record of environmental violations, not just at their TPC Group factories, but also with other SK Capital portfolio firms.

According to EPA data, SK Capital-owned chemical plants in the Houston area increased greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 20 percent between 2014 and 2019.

The pollution from these plants disproportionately burdens communities of color and lower-income areas. This toxic footprint of private equity aligns with the longstanding environmental injustice of siting chemical and petrochemical plants in these neighborhoods, especially along the Gulf Coast. At least 225,000 people live within three miles of SK-owned plants in the Houston area, where 70 percent of the population is Latinx or Black and nearly half (49 percent) lives below the poverty line.

The private equity industry currently owns or has stakes in approximately 175 chemical companies across the United States. The Port Neches explosion was the second private equity-owned petrochemical plant disaster in less than six months.

In June 2019, the Carlyle Group-owned Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery exploded in South Philadelphia, injuring five workers. Because the private equity owner is largely shielded from downside risks of bankruptcy or environmental disaster, it can extract value from the target firm, even at the cost of its long-term productivity or sustainability. [#50]